Introduction

The sex ratio at birth is nearly constant if not artificially manipulated by using sex-selective abortion [1]. The sex ratios at birth in the United States have been stable from 104.6 to 105.9 males (per 100 females) be-tween 1940 and 2002 [2]. However, East Asian countries that shared a traditional culture of son preference reported unnaturally high sex ratios at birth [3]. In China, Taiwan, South Korea, India, and Viet Nam, the sex ratios at birth were 108 or more males (per 100 females) at some point by the early 2000s; this imbalance was attributed to son preference and sex selection [4]. The distortion in the natural sex ratio can have undesirable social consequences, such as a disequilibrium in the marriage market [5,6]. This can further have a negative impact on the psychological well-being of never-married men, such as increased depression, aggression, and suicidal thoughts [7].

The practice of sex selection appeared to increase for higher order births in countries with strong son preference, such as China and Korea, as evidenced by correspondingly rising sex ratios at birth [5]. The sex ra-tio at birth in Korea increased from 108.9, 117.5, 195.9, to 234.4 for the first, second, third, and fourth order births, respectively, in 1990 [8]. The same association between sex ratio and birth order was not observed in other regions. For example, the neonatal sex ratio was not associated with birth order in Denmark and Israel [1,2] and decreased with rising birth order in the United States [9].

Yoo et al. [10] reported a decline in son preference in Korea. Therefore, it is worth reexamining if the sex ratio at birth by birth order has also changed in Korea in recent years. This study aims to analyze secular trends in sex ratios at birth by birth order based on the latest birth records from 1981 to 2017 in Korea in order to inform population policy.

Methods

We extracted birth records from Statistics Korea [11]. Using a total of 21,685,402 births from 1981 to 2017, we calculated and plotted the sex ratio at birth [(number of males/number of females)×100] by year and birth order. Birth orders were classified into three groups: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd and higher birth order. A total of 47,446 births for which birth order was unidentified were excluded from this analysis. To further analyze secular trends in sex ratio at birth by year and birth order, birth data were grouped into a period of 3 to 5 years: 1981-1984, 1985-1989, 1990-1995 … 2010-2014, and 2015-2017. Consistent grouping of 5 years, which was initially intended, could not be achieved due to limited data avail-ability at the time of this study, so that 3 and 4 years were included in the first and last time periods, respectively. Using the period 1981-1984 as the reference group, we conducted a logistic regression analysis to test if there were significant changes in sex ratio at birth for all other periods. For each period, a logistic regression analysis was performed to test if there was a significant change in sex ratio at birth for higher order births by using the first order births as the reference group. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses.

Results

The sex ratio at birth was 109.4 for total births (n=21,685,402) be-tween 1981 and 2017 (Table 1). The sex ratio at birth peaked at 116.5 in 1990 and gradually declined to the lowest point of 105.0 in 2016. A baby born in 1990-1994 was 1.07 times (95% CI: 1.06-1.07) more likely to be male than a baby born in 1981-1984 (Table 2). The odds ratio for a baby born to be male has declined since the mid-2000s and reached 0.98 (95% CI: 0.98-0.99) in 2010-2014.

Table 1

Sex ratio at birth by year in Korea, 1981–2017

Table 2

Logistic regression of sex ratios at birth in Korea, 1981-2017

| Year | Number of births | Sex ratio | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981-1984 | 3,159,669 | 107.3 | 1.00 |

| 1985-1989 | 3,187,862 | 111.0 | 1.03 (1.03-1.04)∗∗ |

| 1990-1994 | 3,526,702 | 114.5 | 1.07 (1.06-1.07)∗∗ |

| 1995-1999 | 3,343,902 | 110.5 | 1.03 (1.03-1.03)∗∗ |

| 2000-2004 | 2,668,928 | 109.2 | 1.02 (1.01-1.02)∗∗ |

| 2005-2009 | 2,298,029 | 106.8 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00)∗∗ |

| 2010-2014 | 2,297,876 | 105.8 | 0.98 (0.98-0.99)∗∗ |

| 2015-2017 | 1,202,434 | 105.5 | 0.98 (0.98-0.99)∗∗ |

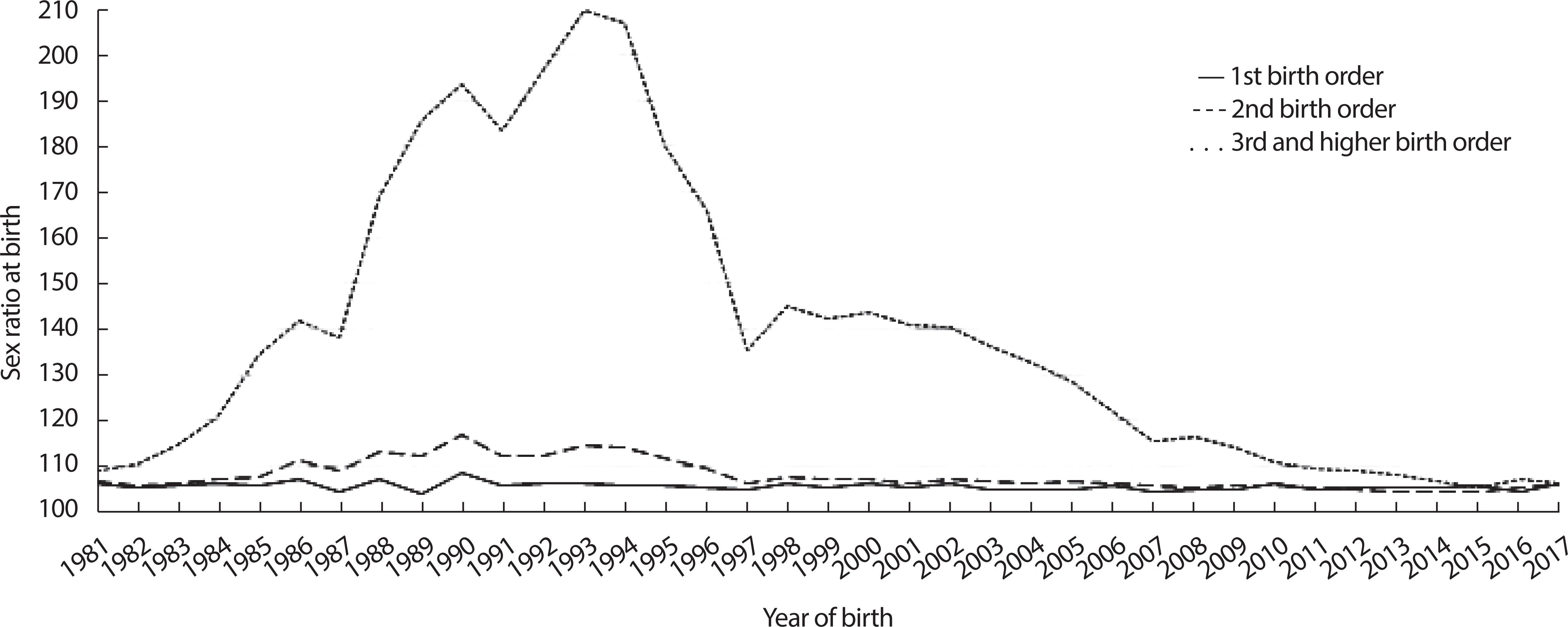

The average sex ratio at birth was highest for the third and higher or-der births (132.0), followed by the second order births (108.8) (Table 3). The sex ratio at birth increased with birth order. The sex ratio at birth ranged from 104.1 in 1989 to 108.5 in 1990 for first-born children, from 104.5 in 2013 to 117.1 in 1990 for second-born children, and from 106.4 in 2017 to 209.7 in 1993 for third and higher order births. The difference in sex ratio at birth between first and third and higher order births was greatest in 1993 (Figure 1). Since then, the difference has gradually de-creased over time and nearly disappeared by the mid-2010s. In 2015, the sex ratio at birth was lower for the second (104.5) and the third and higher order births (105.5) than for the first order births (106.0) (Table 3).

Table 3

Sex ratio at birth by birth order in Korea, 1981-2017

| Year |

Sex ratio by birth order |

Year |

Sex ratio by birth order |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | ≥3rd | 1st | 2nd | ≥3rd | ||

| 1981 | 106.3 | 106.7 | 109.1 | 2001 | 105.4 | 106.4 | 141.1 |

| 1982 | 105.4 | 106.1 | 110.6 | 2002 | 106.5 | 107.2 | 140.6 |

| 1983 | 105.8 | 106.1 | 114.5 | 2003 | 104.8 | 107.0 | 136.2 |

| 1984 | 106.1 | 107.2 | 120.5 | 2004 | 105.1 | 106.2 | 132.4 |

| 1985 | 106.0 | 107.9 | 134.4 | 2005 | 104.8 | 106.6 | 128.3 |

| 1986 | 107.3 | 111.2 | 141.7 | 2006 | 105.8 | 106.1 | 121.9 |

| 1987 | 104.7 | 109.1 | 138.1 | 2007 | 104.5 | 106.0 | 115.7 |

| 1988 | 107.2 | 113.2 | 168.9 | 2008 | 104.9 | 105.6 | 116.6 |

| 1989 | 104.1 | 112.4 | 185.9 | 2009 | 105.1 | 105.8 | 114.3 |

| 1990 | 108.5 | 117.1 | 193.7 | 2010 | 106.4 | 105.8 | 110.9 |

| 1991 | 105.7 | 112.5 | 183.4 | 2011 | 105.0 | 105.3 | 109.5 |

| 1992 | 106.3 | 112.4 | 196.4 | 2012 | 105.3 | 104.9 | 109.2 |

| 1993 | 106.4 | 114.8 | 209.7 | 2013 | 105.4 | 104.5 | 108.0 |

| 1994 | 105.9 | 114.2 | 206.9 | 2014 | 105.6 | 104.6 | 106.7 |

| 1995 | 105.7 | 111.7 | 180.3 | 2015 | 106.0 | 104.5 | 105.5 |

| 1996 | 105.2 | 109.8 | 166.1 | 2016 | 104.4 | 105.2 | 107.4 |

| 1997 | 105.0 | 106.3 | 135.5 | 2017 | 106.5 | 106.1 | 106.4 |

| 1998 | 106.2 | 107.7 | 145.0 | ||||

| 1999 | 105.5 | 107.5 | 142.5 | Total | 105.7 | 108.8 | 132.0 |

| 2000 | 106.2 | 107.4 | 143.6 | (n†) | 10,863,909 | 8,446,458 | 2,327,589 |

A baby born for the second and the third and higher birth order was 1.07 (95% CI: 1.06-1.08) and 1.86 (95% CI: 1.85-1.88), respectively, times more likely to be male than a first-born baby in 1990-1994. Since then, the odds ratio decreased and reached 0.99 (95% CI: 0.99-1.00) for the second order births and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.99-1.02) for the third and higher order births in 2015-2017 (Table 4). The numbers of births in Table 3 and Table 4 excluded births of unclassified birth order.

Table 4

Logistic regression of sex ratios at birth by birth order in Korea, 1981-2017

| Year | Number of births† |

Sex ratio by birth order |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | ≥3rd | 1st | 2nd | ≥3rd | ||

| 1981-1984 | 3,159,645 | 105.9 | 106.5 | 112.2 | 1.00 | 1.01 (1.00-1.01)∗ | 1.12 (1.11-1.13)∗∗ |

| 1985-1989 | 3,187,805 | 105.8 | 110.8 | 149.9 | 1.00 | 1.05 (1.04-1.05)∗∗ | 1.42 (1.40-1.43)∗∗ |

| 1990-1994 | 3,526,536 | 106.5 | 114.1 | 198.4 | 1.00 | 1.07 (1.06-1.08)∗∗ | 1.86 (1.85-1.88)∗∗ |

| 1995-1999 | 3,341,532 | 105.5 | 108.7 | 152.6 | 1.00 | 1.03 (1.02-1.03)∗∗ | 1.45 (1.44-1.46)∗∗ |

| 2000-2004 | 2,651,370 | 105.6 | 106.8 | 139.2 | 1.00 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02)∗∗ | 1.32 (1.31-1.33)∗∗ |

| 2005-2009 | 2,280,921 | 105.0 | 106.0 | 119.2 | 1.00 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02)∗∗ | 1.14 (1.13-1.15)∗∗ |

| 2010-2014 | 2,290,980 | 105.5 | 105.0 | 108.9 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 1.03 (1.02-1.04)∗∗ |

| 2015-2017 | 1,199,167 | 105.6 | 105.2 | 106.4 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 1.00 (0.99-1.02) |

Discussion

Using birth records from 1981 to 2017, we analyzed secular trends in sex ratio at birth in Korea by birth order. The sex ratio at birth in Korea peaked at 116.5 in 1990 and remained at unnaturally high levels until the 2000s. While son preference was an underlying factor to the high sex ratios at birth, the imbalance was likely to be caused by the use of selective abortion based on prenatal sex determination. When the fertility rates were high, families may have achieved their desired sex composition through the random biological process. However, merely the pres-ence of the families who keep bearing children until they give birth to a son did not affect the sex ratio at birth [12]. Instead, the introduction of ultrasound technology in the early 1980s coincided with the increasing sex ratios at birth in Korea [13]. Strong son preference, enabled by the widespread practice of sex selective abortion, may have led to the high sex ratios at birth in Korea in the 1990s when the socially desired family size became smaller [6,14].

While the sex ratios at birth were still increasing in other Asian coun-tries, South Korea was recognized as the first Asian country to reverse the trend of rising sex ratios at birth [15]. In India, the sex ratio at birth was 1.060 in the 1950s, 1.070 in the 1960s, and sharply increased to 1.133 in 2001-2006 [16]. The 2000 census in China showed that there were 120 boys per 100 girls [13]. On the contrary, the sex ratio at birth in Korea, as shown in our data, has gradually declined since the mid-1990s before reaching the natural levels of 105-106 in the early 2010s.

The decrease in the sex ratio at birth in Korea might have been attrib-utable to a decline in son preference. Women’ s odds of stating that they must have a son has declined significantly in Korea from 1991 to 2003 [17]. The proportion of married Korean women reporting that it is either necessary or better to have a son has also declined from 69.2% in 1991 to 40.5% in 2012 [10]. den Boer et al. [15] attributed the decline in son pref-erence in Korea to a number of factors: an effective legal attack on patri-lineality, the decline in the importance of agricultural land as a principal asset which tended to be inherited to sons, the increased provision of so-cial insurance for old age, state advocacy for gender equality, and legal sanctions against physicians practicing fetal sex identification [15]. In fact, the percent of parents stating reliance on sons for old age support has declined for all educational levels from the late 1990s to 2006 in Ko-rea [13]. The Medical Law revised in 1987 included a clause of prohibiting fetal sex identification by medical practitioners, although the provision was ruled unconstitutional in 2008 [18].

In addition to a decline in son preference, a number of other factors such as declining family size, increasing maternal age, and increased number of infants per plural birth might have contributed to the decline in the sex ratio at birth in Korea. These factors were reported to be asso-ciated with a decrease in the sex ratio at birth in other countries [19,20]. For example, A smaller average family size, as reflected in the declining average birth order, was associated with a decrease in the sex ratio at birth in European countries including Denmark [19]. The sex ratio at birth has declined with advancing maternal age up to 27 years in Latin American countries [20]. The sex ratio at birth decreased with increased number of infants per plural birth in Denmark (1980-1993) and in Sweden (1869-2004) [1,21]. The multiple birth rate, measured as the number of multiple births per 1,000 live births, has increased from 10.0 in 1991 to 27.5 in 2008 in Korea [22]. We can also speculate that the declining fertility rates in Korea might have contributed to the decrease in the sex ratio at birth but a future study is needed to examine the relationship.

A study based on all birth records from 1972 to 1990 in Korea showed that the sex ratio at birth did not vary much by birth order (1st to 6th) until 1980; it is only after 1980 that the sex ratio at birth increased with rising birth order [8]. Our data showed that there remained a serious im-balance in the sex ratio at birth by birth order in the 1990s. While the sex ratio for children of the third and higher birth order peaked at 209.7 in 1993, the imbalance in the sex rate at birth for them has persisted un-til the early 2010s, as shown by the results of our logistic regression anal-ysis. The positive relationship between sex ratio at birth and birth order was also observed in other East Asian countries such as China and Tai-wan but not in Western countries [1,3].

Our data indicated that the long-held positive relationship between sex ratio at birth and birth order in Korea has disappeared in recent years. Although the sex ratio for all births has remained high at 132.0 for the entire study period (1981-2017), the annual sex ratio for the third and higher birth orders has become comparable to that for the first and sec-ond birth orders by the mid-2010s. As a result, the huge differences in sex ratio at birth between the first- and the third and higher birth orders observed for period 1989-1994 have gradually declined until they disap-peared in 2015. Our findings suggest that sex-selective abortion was practiced more often for the fetuses of third or higher birth orders in the past but that the disproportional use of the practice by birth order has decreased as son preference declined.

Our analysis of latest birth records showed that although the sex ratio at birth in Korea returned to the natural levels in the late-2000s, the ab-normally high sex ratio for the third and higher birth order persisted until the early 2010s. Consequently, the once considerable variation in the sex ratio at birth by birth order has disappeared only in the mid-2010s. Our findings suggest that son preference, while on the decline in the past several decades, still remained a force that influenced the sex ra-tio at birth in Korea until the mid-2010s. This study was intended to de-scribe trends in the sex ratio at birth based on latest birth records in Ko-rea but not to explain the reasons for changes in the sex ratio, in large part due to the limitation of the data source used in this study. Future research should use other data sources to investigate what has led to the drastic changes in the sex ratio at birth, especially for the third and high-er order births, in Korea.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the sex ratio at birth in Korea has peaked at 116.5 males per 100 females in 1990 and thereafter has gradually declined to the nat-ural levels of 105-106 males per 100 females in the 2010s. For all births between 1981 and 2017, the sex ratio at birth increased with rising birth order. Despite the decrease in the overall sex ratio at birth in Korea, the abnormally high sex ratio for the third and higher birth order disap-peared only in the mid-2010s. Although the decline in the overall sex ra-tio at birth might have been attributable to a decline in son preference, the age-old attitude of parents might have contributed to the persistently high sex ratio at birth especially for the third and higher birth order un-til the early 2010s.