외국의 백신 능동적 감시 시스템 소개

An Introduction of the Active Vaccine Safety Surveillance System in Foreign Countries

Article information

Trans Abstract

Vaccines require higher safety standards than most other medicinal products because they are given to healthy individuals, including infants, children, and elderly. Despite various activities by national agencies, public concern about vaccine safety often arises. Post-marketing activities for vaccine safety can be broadly classified into passive and active surveillances. Many countries as well as Korea operate passive vaccine safety surveillance systems that report adverse events related to vaccines. However, the active surveillance systems operate only in several countries, such as the United States of America (USA), Europe, Canada and Australia. In the US, Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) and Post-Licensure Rapid Immunization Safety Monitoring (PRISM) were developed in 1990 and 2009 respectively for monitoring vaccine actively. In the case of Europe, the Vaccine Adverse Event Surveillance and Communication (VAESCO) consortium was launched in 2008. After the end of VAESCO, the Accelerated Development of VAccine beNefit-risk Collaboration in Europe (ADVANCE) was organized to establish a vaccine benefit-risk monitoring framework in 2013. Canada has been operating a vaccine active monitoring system known as the Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program, ACTive (IMPACT) since 1991. The objective of this review was to describe and compare background, databases, and analysis systems of various vaccine active surveillance systems in the US, Europe, and Canada. We described the examples of studies on the safety of influenza A (H1N1) vaccines carried out in each system. This review could help provide directions for the future development of the ideal active vaccine safety surveillance system in Korea.

서 론

백신은 대규모 인구집단에서 비교적 적은 비용과 노력으로 질병의 발생을 크게 줄일 수 있어 공중보건학적 관점에서 매우 중요하다. 따라서 국가 차원에서 예방접종 지원사업을 실시하는 경우가 많고, 우리나라 또한 만 12세 이하를 대상으로 17종 백신을 무료로 접종하는 어린이 국가 예방접종 지원사업 등을 실시하고 있다. 그러나 특히 백신은 건강한 사람을 대상으로 접종이 이루어지기 때문에 백신의 안전 기준은 다른 의약품에 비해 엄격하고, 경미하거나 드물게 이상반응이 발생하더라도 접종률에 큰 영향을 미칠 수 있다[1,2]. 그러므로 백신에 대한 감시 시스템을 구축하여 백신의 안전성에 대한 근거를 확보하여야 한다.

백신을 비롯한 약물의 이상반응 감시는 자료수집의 적극성에 따라 수동적 감시와 능동적 감시로 구분할 수 있다[3]. 백신의 수동적 감시는 백신을 접종 받은 환자, 접종 의료인 또는 백신 제조 회사 등이 예방접종 후 이상반응에 대해 보고하는 것을 의미하며, 비교적 적은 비용으로 광범위하게 이상반응을 감지할 수 있다는 장점이 있다[4]. 우리나라에서는 1994년에 일본뇌염백신 접종 이후 인과성이 밝혀지지 않은 사망 사례 발생에 따라 국가로부터 백신으로 인한 피해를 보상받을 수 있도록 하는 제도를 신설하여 이상반응 보고를 받기 시작하였다[5]. 이후 2001년부터 의료인의 이상반응 보고를 의무화하였고[6], 현재는 질병관리본부와 한국의약품안전관리원에서 다양한 이해관계자로부터 보고받고 있다[7].

백신의 능동적 감시는 예방접종 자료, 의료 기록, 의료기관 방문 조사 등에서 얻은 다양한 데이터로부터 백신의 이상반응으로 의심되는 사례를 파악하는 것이다[4]. 이는 수동적 감시에 비해 데이터 수집의 완전성과 적시성을 보장할 수 있으며[4], 높은 수준의 감시 시스템은 특정 모집단에서의 백신 효과성 평가와 가속화 승인도 가능하게 할 수 있다[8]. 미국과 유럽 등에서는 백신의 안전성을 조기에 확인할 수 있는 능동적 감시 시스템을 구축하였고, 이를 기반으로 효과적인 예방접종 프로그램과 정책을 실시해 왔다. 그에 반해 우리나라는 대규모 데이터베이스에서 이상반응의 실마리정보(signal)를 지속적으로 감시하는 시스템이 아직 구축되어 있지 않다.

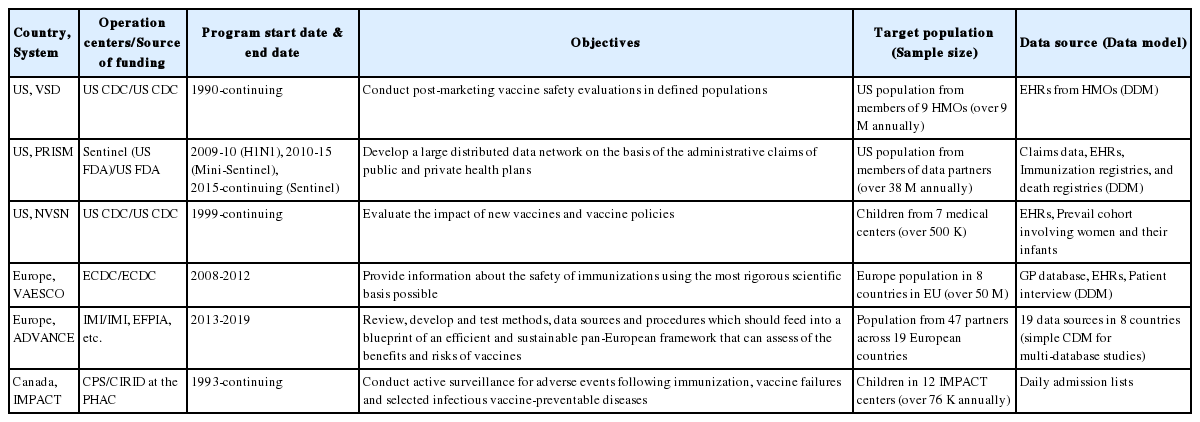

본 연구에서는 미국, 유럽 및 캐나다의 여러 백신 능동적 감시 시스템을 소개하고(Table 1) 각 시스템에서 수행한 신종인플루엔자 A(H1N1) 백신의 안전성 연구를 사례로 기술하여 특징을 비교하고자 하였다. 외국 사례의 조사 내용을 바탕으로 본고를 통해 우리나라에 적합한 백신 능동적 감시 시스템 구축 방향을 제안하고자 한다.

본 론

외국의 백신 능동적 감시 시스템 구축 배경 및 현황

미국

미국에서는 1980년대 디프테리아·파상풍·백일해(diphtheria ·pertussis ·tetanus, DPT) 백신 접종 이후 이상반응을 경험한 사람들이 백신 제조회사를 고소하는 사건이 발생했고, 이로 인해 많은 제조회사들이 재정적 부담을 이유로 백신 생산량을 줄이거나 생산을 중단하였다[9]. 백신 부족현상에 따른 접종률 하락을 우려한 보건당국은 백신으로 인한 이상반응이 발생할 경우 국가 차원에서 보상하는 내용을 포함한 국가아동백신피해법령(National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act)을 1986년에 마련하였다[10].

위 법령의 영향으로 1990년에 미국 질병통제예방센터(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC)는 기존의 수동적 감시 시스템을 새롭게 보완하여 Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS)을 구축하였고, VAERS에서 보고된 백신에 대해 대규모 데이터베이스를 이용하여 적시에 효율적으로 안전성 정보를 제공할 수 있도록 능동적 감시 시스템인 Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD)를 구축하였다[10,11]. VSD 구축 초기에는 건강유지조직(Health Maintenance Organization, HMO)과 메디케이드(Medicaid)에서 매년 수집한 데이터를 이용하여 감시를 수행하였으나, 2005년부터 실시간 이상반응 분석(Rapid Cycle Analysis, RCA) 방법을 도입하면서 주(week) 단위로 사전에 지정한 백신과 이상반응을 감시하게 되었다[11,12].

2009년에 미국 식품의약품안전국(Food and Drug Administration, FDA)에서는 정부의 권고로 기존의 VSD를 확장 및 보완하고자 새로운 H1N1 백신의 능동적 감시 시스템인 H1N1 Post-Licensure Rapid Immunization Safety Monitoring (H1N1 PRISM)을 개발하였다[13]. H1N1 PRISM은 이후 여러 백신에 대해 지속적으로 감시하고자 PRISM으로 변경되어 2010년부터 미니센티넬(Mini-Sentinel)의 일부로 통합되었고[14], 2015년부터는 센티넬 이니셔티브(Sentinel Initiative) 내에서 수행되고 있다[15]. PRISM은 먼저 구축된 VSD보다 훨씬 많은 수의 환자들에 대한 정보를 가지고 있으며[14], 데이터 파트너로부터 얻은 자료를 이용하여 사전에 지정된 백신-이상반응 쌍에 대한 감시 외에도 안전성 문제를 확인하는 연구 및 분석방법 등을 활발히 개발해 오고 있다[16].

유럽

유럽 질병통제예방센터(European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, ECDC)에서는 국가간 데이터 비교 문제를 해결하고 유럽 내 대규모 인구집단을 대상으로 한 백신 안전성 연구를 수행할 수 있도록 2008년에 Vaccine Adverse Event Surveillance and Communication(VAESCO) 컨소시엄을 구축하였다[17,18]. VAESCO에서는 8개 유럽 국가(네덜란드, 노르웨이, 덴마크, 스웨덴, 스페인, 영국, 이탈리아, 핀란드)의 보건의료데이터베이스를 이용하여 감시를 수행하였고[19,20], 사례 정의를 표준화하는 백신 안전성 연구 네트워크인 Brighton Collaboration을 협력 파트너로 두었다[21]. 그러나 ECDC의 예산 부족으로 VAESCO는 약 3년 동안 운영된 후 2012년 9월에 종료되었다[22].

VAESCO의 H1N1 백신 감시에서 나타난 데이터 수집의 제한, 이해관계 충돌, 민관 상호 협력 부족 문제를 해결할 수 있도록 하는 새로운 백신의 유익성-위해성 감시 프레임워크를 개발하고자 Accelerated Development of VAccine beNefit-risk Collaboration in Europe (ADVANCE)가 등장하였다[22]. ADVANCE는 Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI)를 주축으로 구성되었으며 ECDC, European Medicines Agency (EMA), 국가 공중보건 기구, 국가 규제 기관, 백신 제조업체, 의료인 등이 프로젝트에 참여하였다[22,23]. 효율적이고 지속 가능한 민관 협력 백신 감시 체계를 구축하고자 7가지 주제(① 백신 감시의 모범 사례 및 수행 강령, ② 유럽 내 감시 협력 체계 구축, ③ 데이터원, ④ 백신 관련 연구 방법론, ⑤ 감시 수행의 개념 증명 연구, ⑥ 프로젝트 관리 및 의사소통, ⑦ 구현 가능성 분석)로 이루어진 Work Packages (WP)를 구성하였고, 그 결과 백신 유익성-위해성 연구를 위한 수행 강령(Code of Conduct)과 공공-민간부문 협력에 대한 거버넌스 지침이 개발되었다[24-26]. 2013년에 시작된 ADVANCE는 5년 프로젝트로서 2019년 3월에 종료되었고, 이후 개발한 내용을 구현하기 위해 VAccine monitoring Collaboration for Europe (VAC4EU)이 구성되었다[27].

캐나다

1980년대 캐나다 보건 당국(Health Canada)은 어린이용 전세포 백일해 백신(whole-cell pertussis vaccines)의 안전성 우려에 대한 조치로 백신 접종에 따른 상해의 보상 계획을 추진하고자 하였으나 백신과 상해의 연관성 및 심각성에 대한 추정이 불가능하였다[28]. 따라서 우선적으로 이를 추정하기 위해 캐나다 보건 당국 내에 예방접종 부서를 신설하여 안전성 감시를 수행하도록 하였다[28]. 그러나 여전히 백신의 이상반응 위험 증가를 감지하는데 한계가 있었기 때문에 능동적 감시 시스템의 도입이 촉구되었고[28,29], 그 결과 1993년부터 Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program, ACTive (IMPACT)가 시작되었다[30]. 현재 IMPACT는 캐나다 공중보건기구(Public Health Agency of Canada)에서 자금을 지원하여 캐나다소아과학회(Canadian Pediatric Society)가 운영하고 있고, 소아 3차 병원 병상의 약 90%에 해당하는 12개의 IMPACT 센터가 참여하고 있다[30]. IMPACT 센터 내에는 감염질환 전문가로 이루어진 지정된 간호 감시요원(nurse monitors)이 백신으로 예방 가능한 질병(vaccine-preventable disease, VPD)과 예방접종 후 발생한 이상반응에 따른 병원의 입원 사례를 조사하여 보고한다[28,31].

백신 능동적 감시 시스템의 데이터베이스

자료원

본 논문에서 다루고 있는 백신 능동적 감시 시스템에서 주로 이용하는 자료로는 보험청구자료, 전자건강기록 및 백신접종자료 등이 있으며, 데이터 파트너와 협력하여 이를 수집하고 있다. 각 시스템에서는 일정 기준에 따라 데이터파트너를 선정하였는데, VSD에서는 백신 연구 경험과 전산화된 예방접종 데이터베이스의 구축 여부를 고려하여 HMO를 선정하였다[10]. PRISM의 경우 H1N1 PRISM 운영 초기에 당시 데이터의 업데이트 주기와 완전성을 고려하여 4개의 보험회사(Health plan)를 데이터 파트너로 선정하였고, 보험 가입자의 거주지에 기초하여 예방접종 등록자료를 이용할 주(state)를 선정하였다[13]. ADVANCE에서는 다양한 데이터파트너의 데이터베이스 가운데 백신 안전성 연구 참여의 준비성을 고려하여 이용하기 적절한 데이터베이스를 목록화하고자 개발한 ADVANCE International Research Readiness (AIRR) 도구를 통해 연구 수행에 적합한 데이터원으로부터 상위 수준의 자료를 수집할 수 있도록 하였다[32]. IMPACT에서는 지리적 분포와 IMPACT 연구자로 활동하고자 하는 소아 감염병 전문가 여부에 기초하여 데이터를 수집하는 12개의 3차 의료기관을 선정하였다[33].

각 시스템의 데이터원을 살펴보면, 우선 VSD와 PRISM은 각 데이터 파트너로부터 얻은 보험청구자료를 주로 이용하되 중복되는 데이터원을 최소화하여 감시 대상 인구가 최대한 중복되지 않도록 하고 있다[8]. 특히 PRISM에서는 로트 번호 등 추가적인 정보를 얻거나 공공부문이나 약국, 마켓 등에서 납품되어 보험회사에 청구되지 않는 백신의 접종자까지 포함하기 위해 주(state)별 예방접종 등록자료를 보험회사에 가입한 사람들의 정보와 연계하여 활용한다는 특징이 있다[13]. 청구자료에서의 진단 코드를 검증하기 위해 VSD에서는 추가적으로 의료 차트를 검토하거나 환자 인터뷰를 수행하고[12], PRISM에서도 의료 기록을 검토하지만 보험회사가 직접 기록에 접근할 수 없고 보유 기관과의 계약을 통해 접근할 수 있기 때문에 비교적 오랜 기간이 소요될 수 있다[14]. VAESCO에서는 감시 당시 참여 국가의 일반의(general practitioner) 데이터베이스, 병원 전자건강기록, 환자 인터뷰 등을 기본 자료원으로 하였고, 필요 시 네덜란드의 통합일차의료정보(Integrated Primary Care Information), 영국의 임상연구데이터베이스(Clinical Practice Research Database) 등의과거자료도이용하였다[34]. ADVANCE 및 VAC4EU에서는 유럽 내 8개 국가의 병원 데이터, 일반의 데이터베이스, 질병 감시 자료, 코호트 자료 등을 사용한다[35]. 이때 각 데이터베이스마다 포함되는 인구의 규모, 의료 서비스 유형(외래, 입원, 응급실 등), 백신 종류, 실시간에 가까운 감시 가능 여부 등이 판이하기 때문에 연구마다 목적에 적합한 데이터베이스를 선정하여 이용한다[35,36]. IMPACT는 각 센터 내의 간호 감시요원이 환자들의 입원 목록 및 퇴원진단코드 검토, 병동 방문, 감염병 전문가와의 상호작용 등 다양한 방식으로 관심 백신과 건강결과에 대한 데이터를 수집한다[28].

수집 정보 및 구성

백신 능동적 감시에 필요한 정보로는 크게 백신 접종 정보, 진단 정보, 인구집단 정보 등이 있다. 먼저 백신 접종 정보로는 감시하고자 하는 백신의 종류와 접종 날짜, 접종 장소 등이 포함되고, 일부 시스템에서는 이에 더하여 동시 접종 백신, 접종 부위, 백신 제조회사, 로트 번호 등을 수집하기도 한다[10,36,37]. 진단 정보에는 예방접종에 따른 건강결과를 확인하기 위해 입원과 외래, 응급실 등에서의 진단 및 처치 날짜, 진단 및 처치 유형, 입원 경로, 진료 부서 등이 사전에 정의된 코드 체계에 따라 기록된다[10,36,37].

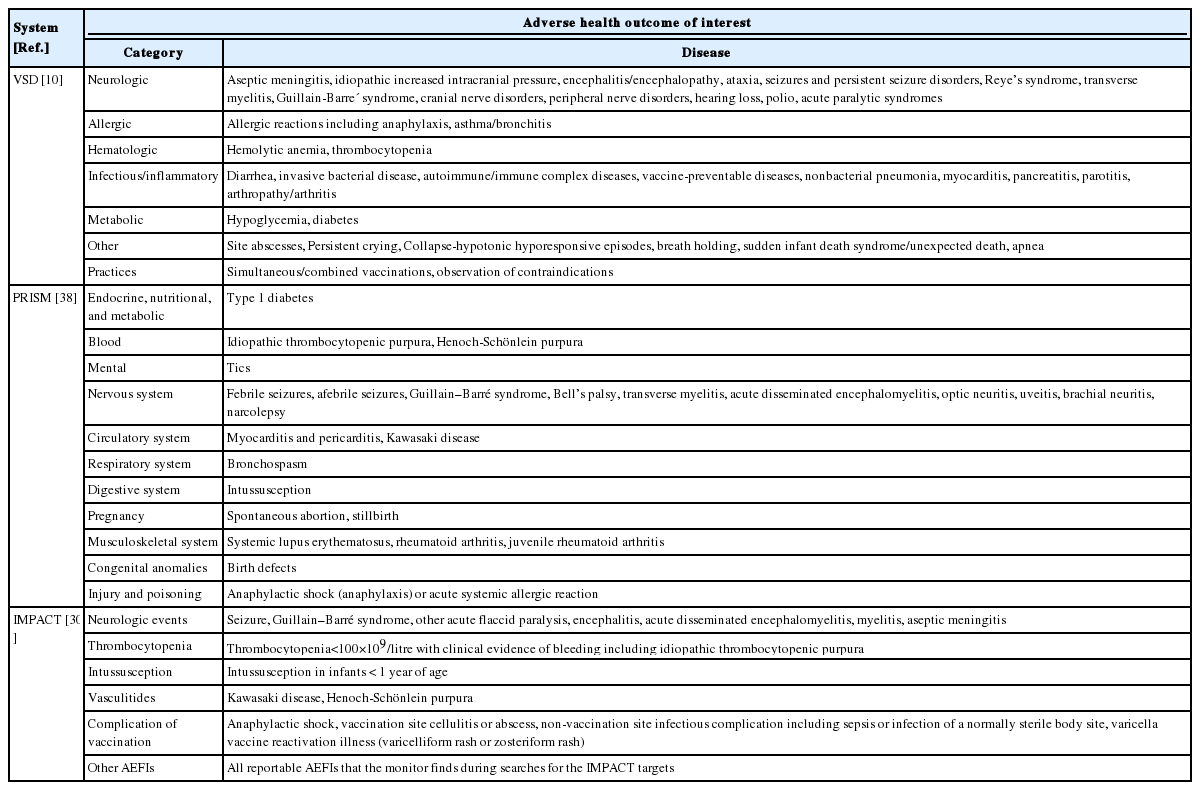

많은 외국의 백신 능동적 감시 시스템에서는 처음 시스템 구축 시 건강결과를 확인하는 알고리즘의 정확성을 검토하거나 모든 입원 사례 대신 백신과 관련성이 높은 이상반응에 대하여 효율적으로 감시하기 위해 이전의 문헌과 자발적 이상반응 보고 자료를 바탕으로 감시 대상을 선정하였다[30,38]. 따라서 VSD, PRISM, IMPACT의 경우 매년 사전에 지정한 건강결과 목록을 바탕으로 감시를 수행해 오고 있다(Table 2) [10,30,38]. 감시 대상 환자에게 수집하는 인구통계학적 정보에는 환자의 연령, 성별, 거주지, 의료보험 등록 정보, 출생 및 사망 정보 등이 있다[10,36,37]. VSD에서는 접종자가 어린이인 경우 부모의 교육수준과 직업, 출생시 체중 및 아프가 점수(Apgar score) 등의 정보를 수집하고, VSD 코호트에서 우편번호와 집주소를 지역 코드를 통해 인구조사 지역과 연결하여 추가적인 사회경제적 정보를 얻을 수도 있다[10].

그 외에도 VSD의 자료와 일부 PRISM 자료에서는 사망원인 정보를 포함하고 있으며[11,37], 임신 기간 중 백신 접종이 영아의 건강에 미치는 영향을 평가하는 연구를 수행하기 위해 두 시스템 모두 엄마의 건강정보와 영아의 출생 및 건강 정보 간 연계 노력을 지속하고 있다[11,39,40]. IMPACT에서는 간호 감시요원이 병원 내에서 이상반응 발생 사례를 직접 보고하기 때문에 이상반응이 발생한 경우 백신 실패에 의한 것인지 혹은 근본적인 면역결핍으로 인한 것인지에 대한 표준화된 면역학적 평가를 수행할 수 있고, 다른 시스템에 비해 발현 증상등 좀 더 세부적인 정보까지 확인할 수 있다[28,31].

자료 형식 및 분석 시스템

대부분의 백신 능동적 감시 시스템에서는 데이터 요소를 정의하여 표준화하는 공통데이터모델(common data model, CDM)과 데이터를 한 곳에 모으지 않고 각 기관 내에 보유하는 분산데이터모델(distributed data model, DDM)을 이용하고 있다. 이 두 모델을 활용하여 능동적 감시 시스템에서는 데이터의 질을 보장하면서 여러 기관의 데이터를 같은 프로그램으로 분석할 수 있다.

VSD는 구축 초기에 매년 HMO들이 환자 개개인의 의료정보 데이터를 CDC로 전송하면 CDC에서 이를 수집하고 병합하는 중앙집중데이터모델(centralized data model)을 이용하였으나, 데이터를 한 곳으로 모으는 것에 대한 개인정보 보호 문제가 제기되면서 기관 내에 개인정보를 보유하되 집적된 데이터나 비식별화된 데이터만을 연구에 이용할 수 있도록 2001년에 DDM을 도입하였다[12]. DDM은 전송 방식에 따라 간접식과 직접식으로 구분한다[12]. 간접식이란 CDC에서 SAS 프로그램을 보안 서버인 허브(hub)에 전송하면 각 HMO에서 허브의 프로그램을 활용하여 기관 내의 자료를 분석하고, 그 결과를 CDC에서 확인할 수 있도록 다시 허브에 전송하는 방식이다[12]. 그에 반해 직접식은 CDC와 각 HMO가 SAS 원격 세션을 통해 SAS 프로그램 및 암호화된 자료를 상호 전송하는 방식이다[12]. DDM의 등장으로 데이터 공유 방식이 바뀌면서 기존에 각 기관마다 매년 데이터 파일을 구축했던 것에서 2005년부터는 실시간에 가깝게 각 기관에서 데이터를 확인할 수 있도록 동적 데이터 파일(dynamic data files, DDF)을 생성하는 방식으로 변화되었다[12].

PRISM에서도 VSD의 간접식 DDM과 같이 환자 수준의 데이터가 아니라 집계된 데이터만 출력하여 공유하는 방식을 이용한다[37]. 센티넬 운영센터(Sentinel Operations Center, SOC)에서 쿼리 프로그램을 센티넬 보안 포털(secure portal) 내에 생성하여 게시하면 각 데이터 파트너가 쿼리를 검토한 후 기관 내에서 보유하고 있는 데이터에 대해 쿼리를 실행한다[41]. 그 결과 산출한 내용을 Sentinel CDM (SCDM)에 따라 구축하여 보안 포털에 제출하면 이를 SOC에서 다른 데이터 파트너들의 결과와 통합하여 Sentinel Distributed Database라 불리는 중앙 저장소에 저장한 후 추가적인 분석에 이용한다[41,42]. 쿼리 프로그램은 사용자 정의(customized) 방식이고, 재사용이 가능하며, 각 데이터 파트너의 다양한 전산 환경에서 효과적으로 실행될 수 있다는 장점이 있다[41].

VAESCO는 유럽 각국의 데이터베이스를 기반으로 약물 안전성을 감시하기 위해 EU-Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) 프로젝트에서 개발한 DDM 방식을 이용하여 운영되었다[43,44]. VAESCO 참여 센터들은 CDM을 통해 환자, 백신, 건강결과에 대한 공통의 입력파일을 국지적으로 생성하여 보관하였고, Jerboa 소프트웨어를 이용하여 각 데이터베이스 내에서 집계 및 비식별화 후 이를 쿼리하여 발생률과 접종률 등의 결과를 산출할 수 있도록 하였다[44]. 산출한 데이터는 네덜란드의 에라스무스 메디컬 센터(Erasmus Medical Center) 중앙 저장소에 암호화 형식으로 전송되었다[44].

ADVANCE에서 개발하여 VAC4EU에서 구현되는 데이터 모델은 CDM과 DDM을 활용하여 VAESCO의 방식과 비슷하게 이루어진다. 먼저 Data Access Providers (DAP)에게 데이터 추출에 관련된 지침과 프로그램이 전송되면, DAP들은 각 로컬의 데이터베이스에서 환자정보, 의료정보, 백신정보와 같은 연구에 필요한 데이터를 추출하고, CDM에 따라 변환하여 입력한다[36]. 이때 각 데이터베이스마다 언어와 코딩 방식이 다양하기 때문에 텍스트 환자 정의를 코드로 매핑하는 CodeMapper를 이용한다[45]. 입력된 파일은 로컬 내에서 R, SAS, Jerboa 소프트웨어 등을 이용하여 공통 모듈 프로그래밍 접근 방식(common modular programming approach)에 의해 데이터셋과 테이블로 변환된다[36]. 변환된 분석 데이터셋은 원격 분석 환경에서 풀링(pooling) 후 연구에 이용된다[36].

IMPACT는 각 센터에서 백신 관련 이상반응이 발생하면 캐나다 공중보건기구에 보고하여 보고자료를 국가 백신 안전성 감시 프로그램인 Canadian Adverse Events Following Immunization Surveillance System (CAEFISS)에서 이용할 수 있도록 한다[30]. 수두와 백일해 등 VPD가 발생한 경우에는 밴쿠버의 IMPACT 센터로 보고하며[28], 그 외에도 FluWatch와 Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (CPSP) 등에 보고되어 다른 감시 시스템의 자료원이 되기도 한다[46].

VSD, PRISM, VAESCO, ADVANCE 모두 CDM을 이용하지만 세부적인 프로세스에는 차이가 있다. VSD와 PRISM의 경우 로컬에서 얻은 데이터 전체를 CDM으로 변환하기 때문에 연구마다 CDM 입력 파일을 생성할 필요가 없다[36]. 반면에 VAESCO와 ADVANCE의 경우 로컬 데이터 중 연구에 필요한 특정 데이터만을 CDM에 따라 입력하므로 실제 이용되는 데이터의 내용은 연구마다 차이가 있다[36]. VSD와 PRISM의 방식이 연구를 수행하기에는 용이하지만 이는 구축하는데 많은 자금과 노력이 필요하고, 특히 유럽의 경우 국가와 데이터 파트너의 다양성으로 인해 구현하는데 더욱 어려움이 있기 때문에 특정 연구별 CDM 방식을 활용하고 있다[36].

각 시스템의 신종인플루엔자 A (H1N1) 백신 능동적 감시 사례

H1N1 바이러스는 2009년 4월 북유럽에서 처음 발생한 이후 당시 세계보건기구에서 전염성 질병 중 최고 등급인 범유행(pandemic)을 선포할 정도로 전세계적으로 유행하였다[47]. 각 국가에서는 국민들에게 H1N1 백신 접종을 실시하였으나 대규모 인구에서의 안전성이 불확실하여 이에 대한 우려가 존재하였다. 특히 1976년 돼지 독감 바이러스(swine flu) 백신에서 대두되었던 길랭-바레 증후군(Guillain-Barré syndrome, GBS)의 위험가능성이 제기되면서[48], H1N1 백신과 접종으로 인한 이상반응 간의 연관성을 확인하는 연구가 여러 능동적 감시 시스템에서 수행되었다(Table 3) [49-54].

당시 미국의 VSD와 PRISM, 영국의 VAESCO에서는 단가와 3가 백신, 생백신과 불활성화 백신과 같은 여러 종류의 H1N1 백신을 노출로 설정하여 이상반응 발생 위험에 대한 연구를 수행하였다. 연구설계로는 자기대조위험기간 연구가 가장 많이 이용되었으며, 드물게 발생하는 GBS의 특성을 고려한 환자-중심 연구 설계와 과거 대조군을 이용한 현재-과거 비교 연구(current vs. historical comparison)도 이루어졌다.

연구 결과를 종합해보면 대부분의 연구에서 H1N1 백신과 길랭-바레 증후군 간에 연관성을 보이지 않았고, 일부 연구에서는 H1N1 단가 불활성화 백신 접종 후 길랭-바레 증후군의 위험이 약간 상승하는 것으로 나타났으나 공변량을 보정하여 추가 분석을 실시했을 때 위험의 증가가 관찰되지 않았다. 당시 H1N1 백신의 안전성 감시는 광범위한 인구 집단에서의 백신 접종 사업을 실시하기 위해 다양한 감시 시스템에서 활발하게 이루어졌을 뿐만 아니라 특히 이를 계기로 H1N1 PRISM과 ADVANCE가 등장하게 되었다는 점에서 중요성을 지닌다.

고 찰

백신 능동적 감시 시스템은 대규모 데이터베이스를 이용하여 백신의 안전성을 감시함으로써 백신에 대한 대중의 신뢰를 높이는 동시에 공중보건 문제가 발생할 경우 신속한 대응이 이루어지도록 한다. 따라서 우리나라를 포함한 많은 국가에서는 이를 구축하기 위해 다양한 노력을 기울이고 있다. 본문에서의 백신 능동적 감시 시스템들은 시스템을 성공적으로 구축하고 운영하기 위해 고려할 점을 시사한다. 먼저, 능동적 감시에는 대부분 전산화된 대규모 연계 데이터가 이용되기 때문에 구축 초기에 파일럿 연구를 실시하여 활용 가능성을 평가하고 문제점을 확인하여야 한다. VSD는 구축 이전 DPT 백신과 신경계 질환(neurologic events) 및 영아돌연사증후군(sudden infant death syndrome)에 대한 두 가지 파일럿 연구를 수행하였고[55,56], PRISM은 H1N1 PRISM과 미니센티넬 PRISM을 거치면서 이후 센티넬 내에서의 백신 감시 틀을 마련하였다[14]. VAESCO에서는 여러 국가의 데이터를 연계하기 이전에 영국과 덴마크의 데이터를 이용한 연구가 이루어졌으며[18], IMPACT에서는 본격적인 감시를 수행하기에 앞서 1991년부터 2년 간의 파일럿 연구를 실시하였다[33]. 다음으로 시스템을 구축한 이후에는 지속성을 확보하기 위한 적절한 방안을 강구해야 한다. 유럽에서는 ADVANCE를 통해 광범위하고 지속적인 백신의 유익성-위해성 감시 틀을 오랜 기간에 걸쳐 구축하였다[25,57]. 또한 시스템이 안정적으로 지속되기 위해서는 참여 인력의 역할도 중요하기 때문에 IMPACT에서는 간호 감시요원이 자원봉사로서 참여함에도 불구하고 만족도를 느끼며 오랜 기간 참여할 수 있도록 백신 감시 데이터를 이용한 논문을 작성할 수 있게 하는 등 적절한 이익을 제공해 오고 있다[33]. 그 밖에도 능동적 감시에는 시판 전 임상시험 대상으로 포함되지 않는 소아, 임신부, 노인과 같은 다양한 인구 하위집단에서의 안전성을 감시하여야 한다. 앞서 언급한 바와 같이 특히 VSD와 PRISM에서는 엄마와 아이의 건강 정보를 연계하여 임신부의 백신 접종을 감시하고[11,40], 추가로 최근 VSD에서는 사회경제적 특성을 실제와 유사하게 반영하고자 사회적 빈곤층에 의료서비스를 제공하는 Safety net 데이터의 통합 모형을 제시하여 시범 연구를 수행하고 있다[58].

백신 능동적 감시 시스템은 백신의 안전성에 관련된 실마리정보를 감지하고 연관성을 확인하여 예방접종 권고사항과 정책 변경의 근거를 제공하는 역할을 수행한다는 점에서 중요성을 지닌다. 한 예로, 홍역·볼거리·풍진·수두(Measles ·Mumps ·Rubella ·Varicella, MMRV) 백신은 허가 전 임상시험에서 발열 발생이 증가하여 추가적으로 VSD와 백신 제조회사(Merck & Co.) 모두 발열과 관련이 있는 열성 발작의 위험에 대한 시판 허가 후 임상시험을 실시하였다[59]. VSD 연구 결과 생후 12-23개월 어린이에서 발작 위험의 실마리정보를 감지하고, 추가적인 연구에서 실마리정보가 실제로 안전성 문제로 인한 것임이 밝혀졌다[59]. 따라서 미국 예방접종자문위원회(Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices)의 2007년 예방접종 권고사항에는 홍역·볼거리·풍진(Measles ·Mumps ·Rubella, MMR) 백신과 수두 백신을 따로 접종하기보다 MMRV 백신을 접종하는 것을 우선시하였으나 2008년에는 감시 중간결과를 고려하여 MMRV 백신의 접종을 우선시 하지 않도록 권고안에 반영하였다[60]. 또한 최종 감시 결과에 따라 2009년에는 보호자가 MMRV 백신을 선호하지 않는 이상, CDC는 생후 12-47개월 사이의 아이들에게는 첫 번째 접종으로 MMR 백신과 수두 백신의 접종을 권고하고, 첫 번째 접종 연령이 생후 48개월 이상이거나 두 번째 접종일 경우에는 MMRV 백신의 접종을 권고하는 것으로 수정하였다[60]. 이처럼 실제 백신의 안전성 문제가 존재하는 경우 능동적 감시 시스템은 이를 신속하게 파악하고 적절한 조치를 취하도록 할 수 있다.

우리나라에서 수행한 백신의 능동적 감시는 대부분 질병관리본부의 예방접종등록자료 또는 특정 의료기관의 자료를 이용한 연구를 수행한 것이다[61-64]. 이러한 연구는 대개 기술 통계를 이용한 현황 조사 중심으로, 백신의 새로운 안전성 정보를 시기적절하게 제공하기에는 한계가 있다. 따라서 우리나라에서도 체계적으로 이상반응의 실마리정보를 밝혀내는 능동적 감시 시스템 구축을 위한 기반을 마련할 필요가 있다. 이를 위해서는 먼저 제도적 기반과 데이터베이스를 구축하는 것이 선행되어야 한다. 능동적 감시를 위해 우선적으로 필요한 자료에는 질병관리본부의 예방접종등록자료와 국민건강보험공단 및 건강보험심사평가원의 청구 자료, 의료기관에서의 전자건강기록 등이 있다. 그러나 현재까지는 각 기관 간 자료 연계의 근거가 되는 제도가 마련되어 있지 않은 상황이므로 백신의 능동적 감시를 위한 데이터 간 연계를 가능하게 하는 제도적인 기반을 먼저 마련할 필요가 있다. 데이터 구조의 관점에서 살펴보면 외국의 경우 대부분 여러 지역이나 국가의 자료를 이용해야 하기 때문에 보안 유지를 위해 DDM을 이용하고 있다. 하지만 우리나라의 경우 단일보험체제로 전국민의 청구 자료를 국민건강보험공단과 건강보험심사평가원에서 보유하고 있기 때문에 전담 부서에서 데이터베이스를 구축하여 관리하는 중앙집중데이터모델을 활용하는 것이 적절할 것으로 보인다. 또한 청구 자료의 특성상 의료기관에서 공단으로 자료가 전달되어 업데이트 되기까지 일정 기간이 소요되기 때문에 이러한 한계를 고려하여 VSD의 RCA와 같이 주(week)별 감시를 수행하지는 못하더라도 가능한 단기로 감시 수행 주기를 설정해야 할 것이다.

결 론

외국의 사례를 통해 제시한 바와 같이 백신의 능동적 감시 시스템은 새로운 백신이 도입되거나 위험성이 제기될 경우 조기에 안전성 근거를 제공할 수 있다는 점에서 중요하다. 그러나 감시 시스템을 구축하고 운영하기 위해서는 전반적인 기반 마련에서부터 연구 수행 및 결과 도출에 걸쳐 고려할 점이 많기 때문에 이미 구축되어 있는 외국의 사례를 참고하여 기틀을 마련하는 것이 바람직할 것으로 사료된다. 특히 체계적인 감시를 수행하기 위해 백신 능동적 감시 담당 부서, 데이터 제공 기관, 자문과 의사결정을 제공하는 전문가 협의체 간 네트워크를 아우르는 전체적인 거버넌스를 수립해야 한다. 또한 외국의 사례에서와 같이 데이터베이스에 가장 적절한 연구설계 및 분석 방법을 지속적으로 개발하고 검증하는 과정을 수행하는 것 역시 필수적이다. 백신 능동적 감시 시스템은 백신의 안전성을 감시하는 것이 주된 목적이지만, 그 외에도 VPD의 역학 연구, 백신 접종 권고사항 이행 현황, 백신의 효과성 평가까지 다방면으로 활용 가능하기 때문에 활용도가 높다. 체계적으로 구축한 백신 능동적 감시 시스템에서 얻은 정보는 백신의 안전성을 보장하고 안정적인 접종률을 유지하면서 향후 효과적인 공중보건 정책과 국가 예방접종 사업을 실시하는데 큰 기여를 할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Government-wide R&D Fund project for infectious disease research, HG18C0067).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.