성인 여성의 갑상샘 기능과 우울증 및 스트레스

Relationships between Thyroid Function and Depression and Stress in Adult Females

Article information

Abstract

Objectives

The number of thyroid-related patients in Korea is steadily increasing. Women received treatment for hypothyroidism5.3 times more than men and treated for hyperthyroidism 2.5 times more than men in 2018. The purpose of this study was to find out the relationships between thyroid function and depression and stress in adult females.

Methods

This study was conducted on 2,991 adult females who participated in the 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Participants were classified as normal, hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism according to the thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (fT4) level. To examine the dose-response relationship, the participants were categorized by quartiles of the TSH and fT4 level and analyzed through multiple logistic regression on depression and stress.

Results

Hypothyroidism with high TSH level group had 57% lower risks for depression (odds ratio, OR=0.43, 95% confidence interval, 95% CI=0.19-0.95, p =0.004). The lowest TSH quartile was 2.79 times more likely to have depression compared to the highest quartile (OR=2.79, 95% CI=1.32-5.92, p =0.020). The lowest TSH quartile was 40% lower risks for stress than those in the highest TSH quartile (OR=0.60, 95% CI=0.45-0.80, p <0.001).

Conclusions

We demonstrated that the relationships between thyroid function and depression and stress remain poorly defined in adult females. Further studies are required to confirm the exact cause-effect relation of this association.

서 론

보건복지부의 ‘2016년도 정신질환실태 역학조사’ 결과에 따르면 국내의 우울증 환자수는 61만 명으로 추산된다[1]. 우울증의 평생 유병률은 남성은 3.0%, 여성은 6.9%로 여성이 남성보다 2배 이상 높았다[1]. 우울증은 보편적으로 발생하는 정신질환 가운데 하나로 전 세계적인 건강문제의 주요 원인으로 꼽히며, 우울증을 앓는 사람의 자살 사망 위험은 정상인에 비해 20배 이상 높았다[2]. 우울증은 자살뿐만 아니라 뇌졸중 및 심혈관 질환을 포함한 기타 질병에 영향을 미치고, 인지 적, 사회적 기능을 손상시켜 업무 수행의 저하를 초래하여 개인, 가족 그리고 사회 전반에 경제적 영향을 미치고 삶의 질을 하락시킨다[2]. 특히, 모성 우울증은 아기의 건강과 발달에 지장을 주어 미래 세대의 정신 건강에 장기적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다[2]. 우리나라의 갑상샘 질환 환자 수는 꾸준히 증가하고 있으며, 2018년 기준으로 갑상샘 기능 저하증은 여성이 남성에 비해 5.3배, 갑상샘 기능 항진증은 2.5배 많이 진료를 받은 것으로 나타났다[3]. 갑상샘 질환이 여성에게 높게 발생하는 것으로 보아 여성 호르몬에 의한 면역계의 이상으로 인해 발생할 수 있으며[4], 남성보다 여성에게서 혈중 갑상샘자극호르몬(thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH) 농도에 대한 유전적 영향이 더 두드러졌고, 이는 여성의 갑상샘 기능에 영향을 미치는 요인이 될 수 있다[5]. 또한 여성의 높은 스트레스는 혈중 TSH 농도를 증가시켜 갑상샘 질환을 유발하는 것으로 추정된다[6]. 갑상샘 기능이 우울증 및 스트레스에 미치는 영향은 아직 명확하게 밝혀지지 않았으나, 예측 가능한 이론은 시상하부-뇌하수체-갑상샘 축에서 갑상샘 자극호르몬 방출호르몬(thyrotropin-releasing hormone, TRH)이 분비되면서 뇌하수체를 자극하고, 뇌하수체에서 TSH를 분비하여 갑상샘을 자극하면 갑상샘호르몬이 분비된다[7]. 그러나 시상하부-뇌하수체-갑상샘 축의 기능 이상으로 갑상샘호르몬이 원활하게 분비되지 않으면 과도한 부신피질자극호르몬방출호르몬(corticotropin-releasing hormone, CRH)과 코르티솔(cortisol)의 분비가 촉진되어 뇌의 구조적 및 기능적 변화로 인해 우울증을 유발할 수 있다[8].

남녀 모두를 대상으로 한 과거 연구에서 갑상샘 기능 저하증, 항진증 환자는 건강한 사람들에 비해 더 심한 우울 증상을 보였고, 삶의 질이 저하되었다[9]. 60세 이상의 갑상샘 기능 저하증 환자와 우울증 사이의 연관성을 보였고[7,10], 생식 가능한 연령대의 여성을 대상으로 한 연구에서 높은 혈중 TSH 농도는 높은 스트레스 척도점수를 나타내며 양의 상관관계를 보였다[11]. 그러나 다른 연구에서는 혈중 TSH 농도와 우울증은 통계적 유의성을 보이지 않았고[12], 노인에서 갑상샘 기능 저하증, 항진증은 우울증과 연관성이 없었다[13]. 다양한 선행연구들에서 갑상샘 기능과 정신건강의 관련성을 조사하였으나, 일관된 결과를 보이지 않아 갑상샘 기능이 정신건강에 미치는 영향에 대해서는 아직 논쟁의 여지가 있다. 여성은 임신과 출산 그리고 폐경으로 인한 호르몬 불균형에 의해 면역체계에 변화를 일으켜 남성보다 갑상샘 질환의 발생이 높아지고 있다[14,15]. 갑상샘 질환과 우울증 및 스트레스는 여성의 전 연령대에 걸쳐 분포하므로 모두 성인 여성에게서 흔히 발생하는 질환 중의 하나이다[3,16]. 그러나 국내에서 성인 여성만을 대상으로 하여 갑상샘 기능과 우울증 및 스트레스의 연관성에 대해 조사한 연구는 아직 보고되지 않았다. 따라서 본 연구를 통해 혈중 TSH와 fT4 농도의 상승과 저하에 따른 우울증 및 스트레스와의 관련성을 조사하고자 하였다.

연구 방법

연구대상 및 자료수집

본 연구는 제6기(2013-2015년) 국민건강영양조사의 자료를 이용하였다. 연구의 대상자인 20세 이상의 성인 여성 10,199명 중에서 혈중 TSH와 fT4농도의 데이터가 유효하고, 우울증 선별도구(Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9) 문항 및 스트레스 인지율에 응답한 대상자 2,991명을 선정하였다. 국민건강영양조사의 표준화된 설문지를 이용하여 얻은 기본 변수자료에서 나이와 성별, 소득수준, 교육수준, 고용형태에 대한 자료를 수집하였다. 소득수준은 월평균 소득에 따라 4분위수로 조정한 값을 사용하였으며, 교육수준은 초등학교졸업이하, 중학교졸업, 고등학교졸업, 대학졸업이상으로 구분하였다. 고용형태는 관리자, 전문가 및 관련 종사자와 사무종사자를 white collar로 분류하였고, 서비스 및 판매 종사자, 농림어업 숙련 종사자, 기능원, 장치기계조작 및 조립종사자와 단순노무종사자를 blue collar, 무직(주부, 학생)을 미취업자로 정의하였다. 건강설문조사에서 결혼상태, 흡연, 음주, 신체활동에 대한 자료를 수집하였고, 결혼 상태는 기혼과 그 외(미혼, 별거, 사별, 이혼)로 나누었다. 흡연은 평생 담배 5갑 이상을 피웠고 현재 담배를 피우는 경우, 음주는 최근 1년 동안 월 1회 이상 음주한 경우로 정의하였다. 신체활동은 걷기 실천율(최근 1주일 동안 걷기를 1회 30분 이상, 주 5일 이상 실천한 분율) 또는 중등도 신체활동 실천율(최근 1주일 동안 평소보다 몸이 조금 힘들거나 숨이 약간 가쁜 중등도 신체활동을 1회 30분 이상, 주 5일 이상 실천한 분율) 또는 격렬한 신체활동 실천율(최근 1주일 동안 평소보다 몸이 매우 힘들거나 숨이 많이 가쁜 격렬한 신체활동을 1회 20분 이상, 주 3일 이상 실천한 분율)로 정의하였다. 검진조사에서 체질량지수(body mass index, BMI), 고혈압, 당뇨병, 요중 요오드 배출량에 대한 자료를 취득하였으며, BMI 범주는 18.5 kg/m2 미만을 저체중, 18.5-24.9 kg/m2를 정상, 25 kg/m2 이상을 비만으로 구분하였다. 고혈압은 수축기 혈압 ≥140 mmHg 또는 이완기 혈압 ≥90 mmHg 또는 고혈압 약을 복용 중인 사람으로 정의하였고, 당뇨병은 공복혈당 ≥126 mg/dL 또는 의사진단을 받았거나 혈당강하제를 복용하거나, 인슐린주사를 투여 받고 있는 사람으로 정의하였다. 요중 요오드 배출량은 체내 요오드가 25-49 µg/L 미만으로 배출이 되면 중등도 요오드 결핍증으로 평가되기 때문에 <40 µg/L, ≥40 µg/L로 나누었다[17]. 검사는 미국의 유도 결합 플라즈마 질량 분석기(inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer, ICP-MS)검사방법으로 Perkinelmer사 Perkinelmer ICP-MS 장비를 이용하여 측정되었다. 본 연구는 서울시립대학교 생명윤리위원회의 심의 면제 승인(UOS-IRB-2020-25)을 받았다.

연구도구

갑상샘 기능을 평가하는 검사인 혈중 TSH와 fT4 그리고 요중 요오드 배출량은 만 10세 이상의 조사대상자 중 2,400명을 부표본추출하여 실시하였다. 혈중 TSH와 fT4는 전기화학발광 면역분석법(electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay, ECLIA) 검사방법으로 독일의 Roche사 Cobas8000 E-602 장비를 이용하여 측정되었다. 대상자들의 우울증은 PHQ-9을 사용하여 평가하였다. PHQ-9 점수 10점 이상은 중등도 이상의 우울증에 대한 민감도 88%, 특이도 88%를 보였으며, 진 단의 정확도가 우수하여 신뢰할 수 있는 우울증 척도이다[18]. PHQ-9 점수에 따라 5-9, 10-14, 15-19, 20-27로 구분하여 각각 경도, 중등도, 중증, 고도로 나타냈고, 본 연구에서는 PHQ-9 총점 27점 중 10점 이상을 우울증으로 분류하였다[18]. 스트레스는 국민건강영양조사 설문지에서 평소 일상생활 중의 스트레스를 ‘대단히 많이’ 또는 ‘많이’ 느끼는 편이라고 응답한 사람 수로 정의하였다.

통계분석

갑상샘 기능과 우울증 및 스트레스와의 관련성을 규명하기 위하여 공변량을 보정한 후, 복합표본 다중 로지스틱 회귀분석을 수행하였다. 혈중 TSH와 fT4 농도에 따라 대상자를 정상(TSH: 0.4-4.0 μIU/mL, fT4: 0.9-1.7 ng/dL), 갑상샘 기능 저하증(TSH: >4.0 μIU/mL, fT4: <0.9 ng/dL), 갑상샘 기능 항진증(TSH: <0.4 μIU/mL, fT4: ≥1.8 ng/dL)으로 분류하였고, 용량-반응 관계를 살피기 위하여 대상자들을 4분위수로 분류하였다. 잠재적 공변량은 선행연구의 결과를 고려하여 나이, 소득수준, 교육수준, 고용형태, 결혼상태, 흡연, 음주, 신체활동, BMI category, 고혈압, 당뇨병, 요중 요오드 배출량으로 설정하였다[19–24]. 본 연구는 SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) 프로그램을 사용하여 분석하였고, 모든 분석의 통계적 유의 수준은 0.05 미만으로 설정하였다.

연구 결과

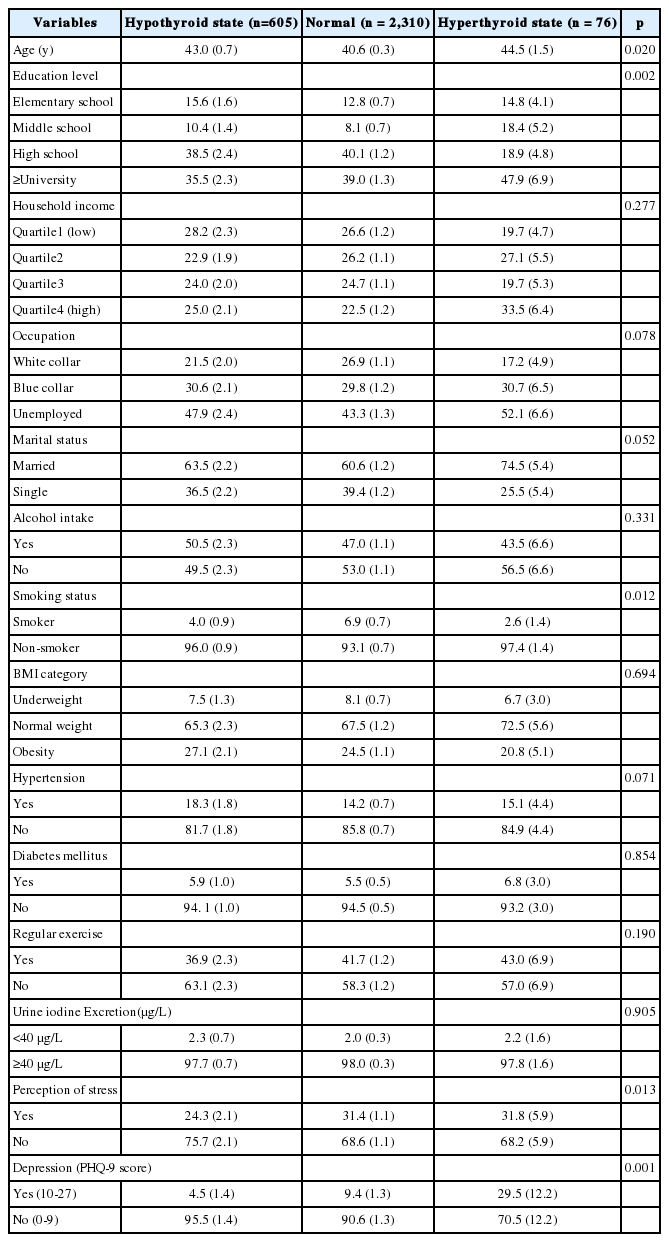

본 연구의 대상자 2,991명의 평균 연령은 41.1세이었고, 연령대별 분포에 따라 분석한 결과, 20-30대의 평균 연령은 29.3세, 40-50대는 49.7세, 60대 이상은 65.2세이었고, 각각 40.9%, 39.9%, 19.2%의 분포를 보였다. 혈중 TSH와 fT4를 농도에 따라 정상, 갑상샘 기능 저하증, 갑상샘 기능 항진증으로 분류하여 분석한 결과, 정상군의 평균 연령은 40.6세, 갑상샘 기능 저하증군은 43.0세, 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 44.5세로 정상군이 갑상샘 기능 저하증, 항진증군 보다 유의하게 낮았다(Table 1). 교육수준은 갑상샘 기능 저하증군과 정상군에서는 고등학교졸업이 각각 38.5%, 40.1%로 가장 많았고, 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 대학졸업 이상이 47.9%로 가장 많은 분포를 보였다. 흡연상태는 정상군, 갑상샘 기능 저하증군, 갑상샘 기능 항진증군 모두 비흡연자가 각각 93.1%, 96.0%, 97.4%로 통계적으로 유의하게 많았다. 정상군의 대상자는 2,310명(77.2%)으로 가장 많았고, 갑상샘 기능 저하증군은 605명(20.2%), 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 76명(2.5%)이었다. 정신건강상태에 대하여 비교했을 때, 정상군의 스트레스와 우울증은 각각 31.4%, 9.4%였으며, 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 정상군에 비해 스트레스(31.8%)와 우울증(29.5%)이 유의하게 더 높았으나, 갑상샘 기능 저하증군은 정상군에 비해 유의하게 낮은 스트레스(24.3%)와 우울증(4.5%)을 보였다.

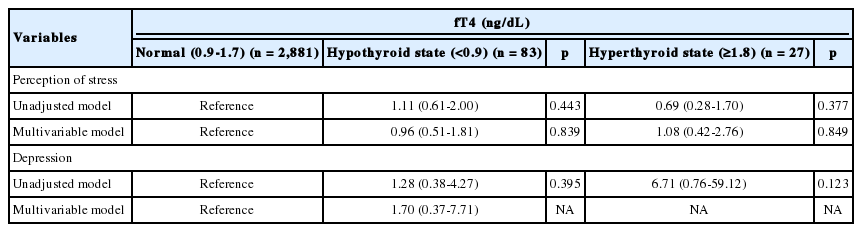

혈중 TSH 농도가 정상인 대상자들에 비교하여, 혈중 TSH 농도가 높은 갑상샘 기능 저하증군의 우울증에 대한 교차비(odds ratio, OR)는 57% 낮았다(OR=0.43, 95% confidence interval, 95% CI=0.21-0.91, p =0.001) (Table 2). 공변량을 보정한 후 분석한 결과에서도 갑상샘 기능 저하증군은 정상인 대상자에 비해 우울증에 대한 교차비가 57% 낮았다(OR=0.43, 95% CI=0.19-0.95, p =0.004). 공변량을 보정하지 않은 분석에서 혈중 TSH 농도가 낮은 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 혈중 TSH 농도가 정상인 대상자에 비해 우울증의 교차비가 4.13배 높았다(OR=4.13, 95% CI=1.28-13.30, p =0.002). 그러나 공변량을 보정한 후에는 갑상샘 기능 항진증군과 우울증은 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다. 또한, 보정 후에 혈중 TSH 농도와 스트레스는 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다. 혈중 fT4 농도에 따른 갑상샘 기능과 우울증 및 스트레스와의 관계는 공변량 보정에 상관없이 유의하지 않았다(Table 3).

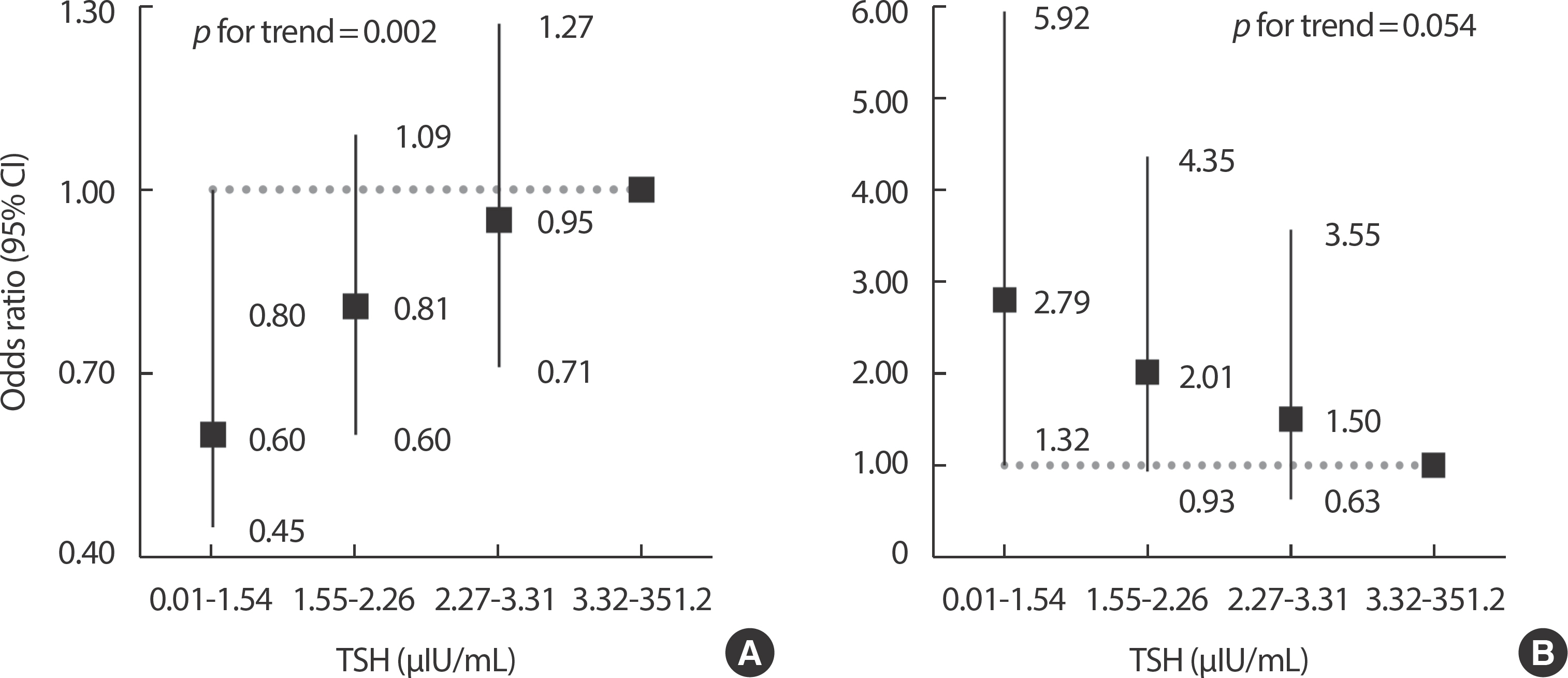

또한, 용량-반응 관계를 살피기 위하여 혈중 TSH와 fT4 농도에 따라 대상자들을 4분위수로 분류하고 다중 로지스틱 회귀분석을 통해 분석하였다. 혈중 TSH 농도가 가장 낮은 4분위의 대상자(0.01-1.54 μIU/ mL)는 가장 높은 대상자(3.32-351.2 μIU/mL)에 비해 우울증의 교차비 가 2.79배 높았다(OR=2.79, 95% CI=1.32-5.92, p =0.020, p for trend=0.054) (Figure 1). 혈중 TSH 농도가 가장 낮은 4분위의 대상자는 가장 높은 대상자에 비해 스트레스에 대한 교차비가 40% 낮았다(OR=0.60, 95% CI=0.45-0.80, p <0.001, p for trend=0.002). 그러나 혈중 fT4 농도와 우울증 및 스트레스와의 관계는 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다(Figure 2).

Adjusted odds ratio of stress (A) and depression (B) according to the quartile of TSH level. Each model controlled for age, education level, house-hold income, occupation, marital status, alcohol intake, smoking status, body mass index category, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, regular exercise, and urine iodine excretion. TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted odds ratio of stress (A) and depression (B) according to the quartile of fT4 level. Each model controlled for age, education level, house-hold income, occupation, marital status, alcohol intake, smoking status, body mass index category, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, regular exercise, and urine iodine excretion. fT4, free thyroxine; CI, confidence interval.

고찰 및 결론

본 연구는 한국 성인 여성의 갑상샘 기능과 우울증 및 스트레스와의 관련성에 대하여 조사하였다. 본 연구에서 갑상샘 기능 저하증은 우울증과 통계적 유의성을 보였고, 혈중 TSH 농도가 가장 낮은 4분위의 대상자는 가장 높은 대상자에 비해 우울증의 교차비가 2.79배 높았다. 혈중 TSH 농도가 증가함에 따라 스트레스에 대한 교차비도 증가하는 경향을 보이며 혈중 TSH 농도와 스트레스는 양의 상관관계를 보였다(p for trend=0.002). 혈중 fT4 농도와 우울증 및 스트레스는 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다.

본 연구와 유사한 결과로 Lee et al. [24]의 연구에서는 혈중 TSH 농도가 가장 높은 3분위(4.77±1.91 mIU/L)의 여성들이 우울 증상의 유병률이 약 35% 낮았고, 혈중 fT4 농도와 우울 증상은 관련이 없었다. 본 연구의 대상자와는 달리 남녀 모두를 대상으로 한 Medici et al. [25]의 연구에서는 혈중 TSH 농도가 가장 낮은 3분위(0.3–1.0 mU/L)의 대상자는 가장 높은 3분위(1.6–4.0 mU/L)의 대상자에 비해 우울 증상뿐만 아니라, 역학연구 우울척도(Center for Epidemiological Studies-De-pression Scale) 점수가 16점 이상이 될 위험이 증가하였다. Engum et al. [26]의 연구에 따르면 정상군(0.2-4.0 mU/L)에 비해 갑상샘 기능 저하증군(TSH>4.0 mU/L)은 우울증의 위험이 낮았고, 갑상샘 기능 항진증군(TSH<0.2 mU/L)은 우울증의 위험이 유의하게 증가하지 않아 갑상샘 기능 항진과 우울증 사이의 연관성은 발견되지 않았다. 갑상샘 기 능 저하증군에서 우울증의 위험이 낮아진 이유는 갑상샘 기능 저하증은 신진대사의 속도를 저하시킬 수 있고, 이는 신체적, 인지적 기능의 상태를 유지하는데 도움이 될 수 있어[27], Park et al. [28]의 과거연구에서 갑상샘 기능 저하증은 신경정신계 질환의 위험 증가와 관련이 없었던 것으로 보여진다.

본 연구에서 혈중 TSH 농도에 따라 정상, 갑상샘 기능 저하증, 갑상샘 기능 항진증으로 분류하여 분석한 결과, 혈중 TSH 농도가 낮은 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 정상군에 비해 우울증의 교차비가 4.13배 높았으나, 공변량을 보정한 후 분석한 결과에서는 갑상샘 기능 항진증군과 우울증은 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다. 보정 후 통계적 유의성이 사라진 것은 전체 대상자 중에서 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 76명(2.5%)이었고, 갑상샘 기능 항진증군 중에서 우울증이 있는 대상자의 수는 5명으 로 정상군(66명)과 갑상샘 기능 저하증군(11명)에 비해 상대적으로 적은 대상자 수를 보였고, 상당히 넓은 범위의 신뢰구간을 나타내며, 보정 후에 통계적 유의성이 사라지는 경향을 보였다고 생각된다. 혈중 fT4는 공변량 보정에 관계없이 우울증 및 스트레스와 통계적으로 유의하지 않았다. 본 연구의 대상자와는 달리 남녀 모두를 대상으로 한 Fountoulakis et al. [29]의 연구에서는 주요우울장애가 있는 환자들의 혈중 TSH와 fT4의 농도가 대체로 정상 범위 내에 있는 것으로 확인되었으며, 일반적으로 갑상샘 기능 이상이 우울증을 유발하지는 않지만 자가면역이 활성화되는 과정에서 갑상샘에 영향을 미치게 되었을 수 있다고 제언하였다.

용량-반응 분석결과, 혈중 TSH 농도가 가장 낮은 4분위의 대상자(0.01-1.54 μIU/mL)는 가장 높은 4분위의 대상자(3.32-351.2 μIU/mL)에 비교하여 스트레스에 대한 교차비가 40% 낮았으나, 우울증의 교차비는 2.79배 유의하게 높은 결과를 보였다. 여성의 우울증 상태에서는 불면, 식욕부진, 피로감 그리고 쾌락을 느끼지 못하는 무쾌감증과 같은 증상이 나타나고[30,31], 무쾌감증은 무기력증과 유사한 증세를 보이며 감정의 변화에 상대적으로 영향을 적게 받을 가능성이 있다. 또한 본 연구에 사용된 스트레스척도는 자가보고형 검사이므로 스트레스에 대한 인지를 과대평가하거나 과소평가했을 가능성이 있기 때문에 스트레스에 대한 교차비가 감소하는 결과를 도출하였다고 생각된다. Grabe et al. [32]의 연구에서 혈중 TSH 농도가 <0.1 mIU/ml인 갑상샘 기능 항진증군은 대조군(0.3-3 mIU/l)에 비해 정신적인 고통을 더 적게 느꼈고, Schlote et al. [33]의 연구에서는 갑상샘 기능 항진증군(TSH< 0.21 mU/L)은 정상군(0.21-3.5 mU/L)에 비하여 더 좋은 기분을 보였고, 더 적은 민감한 기분과 관련이 있었다. 그러나 본 연구에서 혈중 TSH 농도에 따라 정상, 갑상샘 기능 저하증, 갑상샘 기능 항진증으로 분류하여 분석한 결과에서는, 혈중 TSH와 스트레스는 통계적 유의성을 보이지 않았다. 갑상샘 기능 항진증의 대표적인 질환 중 하나인 그레이브스병(Graves’ disease)은 과도한 스트레스가 면역체계의 변화를 일으켜 발생할 수 있다는 연구가 있으나[34,35], 지난 15년 동안 수행된 선행연구를 바탕으로 분석한 문헌 고찰에 따르면, 여성의 자가면역성 갑상샘 질환과 시상하부-뇌하수체-갑상샘 축의 기능 사이에 인과관계가 있는지 확인한 결과, 스트레스에 의한 자가면역성 갑상샘 질환의 발생원인에 대해서는 명확한 메커니즘을 밝혀낼 수 없었다[36]. 따라서 갑상샘 기능과 스트레스 사이의 연관성에 대해 명확하게 규명하기 위해서는 추가적인 연구가 필요하다고 사료된다.

본 연구는 다음과 같은 강점을 가진다. 첫째, 한국 성인 여성의 혈중 TSH와 fT4 농도에 따른 우울증 및 스트레스에 대한 관련성을 확인한 첫 연구이므로, 본 연구는 추후 성인 여성의 갑상샘 질환과 관련된 연구의 기초자료로 활용될 수 있을 것이다. 둘째, 본 연구는 국민건강영 양조사의 대규모 데이터를 기반으로 복합표본 자료분석 방법을 이용한 연구이므로 그 결과가 한국 성인 여성에 대한 대표성을 가진다. 본 연구는 몇 가지 제한점을 가진다. 먼저 본 연구는 단면 연구이기 때문에 혈중 TSH와 fT4 농도에 따른 우울증 및 스트레스의 교차비를 구해 연관성을 보여줄 수는 있지만 인과관계를 명확히 증명하기에는 어렵다는 단점이 있다. 따라서 역의 인과관계의 가능성을 배제할 수 없다. 둘째, 본 연구는 성인 여성만을 대상으로 한 연구로 본 연구결과를 남성이나 미성년자로 확대하여 적용하기에는 어렵다. 셋째, 갑상샘 기능의 지표가 되는 혈중 fT4 농도의 정상 범위가 0.9-1.7 ng/dL로 아주 좁은 범위를 가지고 있어서 대상자 중 정상 범위 미만은 83명(2.6%), 정상 범위 이상은 27명(0.8%)에 불과하여 통계분석 결과의 견고성(robust-ness)을 확보하기 어려웠다. 넷째, 본 연구에서 우울증의 유무를 평가하는데 사용된 PHQ-9은 전문의의 진단을 통해 우울증을 평가받은 것이 아닌 자가보고형 평가 척도이기 때문에 우울 증상의 심각성을 과대평가하거나 과소평가했을 가능성이 있다. 다섯째, 본 연구에서는 신뢰도와 타당도를 확보한 검증된 측정도구가 아닌 자가보고형 설문지를 통해 스트레스를 정의하였으므로, 측정과정에서 오류 발생의 가능성이 있고, 객관성 확보가 어려워 스트레스 지표로 활용하기에는 한계가 있다.

결론적으로 우리는 한국 성인 여성의 혈중 TSH, fT4 농도의 상승과 저하에 따른 우울증 및 스트레스 사이의 뚜렷한 연관성을 발견하지 못했으나, 일부 유의한 관계를 발견할 수 있었다. 정확한 인과관계를 파악하기 위해서는 장기적인 추적관찰 연구가 필요할 것으로 여겨진다.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.